By Fanny Malinen

Tonight, England is playing Iceland. When the small nation qualified to the knock-out stage, BBC presenter reminded home audiences that England has never lost to Iceland in a major tournament. But it is also true that Iceland has never lost a game in one.

Iceland, of course, has never played in the Euros before and are the smallest country ever to do so. It has a population of 330,000 – by coincidence, the same as Leicester. 10-15% of Icelanders are currently in France, following their team making history.

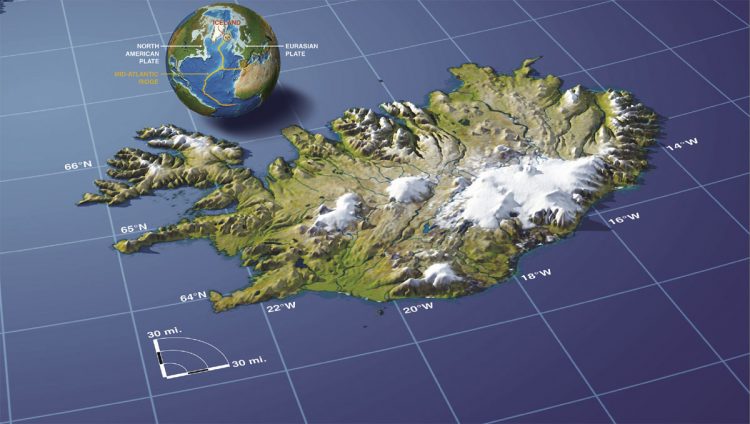

Fun football facts aside, what do we really know about the island of ice and fire? The geysers, volcanoes – especially the one that covered much of the airspace over Northern Atlantic in ash in 2009.

But there is more to Iceland than that, even more than Björk.

Following the Panama Papers’ revelations in April, Icelanders took to the streets and ousted their government. The mistrust stemmed from the PM and other senior cabinet officials having money invested in tax havens.

This was not the first time in the last decade the island had a peaceful revolution. The 2008 crash hit the country harder than many others, and all three of its major banks collapsed. A wave of protests dubbed ‘the Pots and Pans Revolution’ swept the old government to history.

The new parliament initiated a process of crowd-sourcing a new constitution. Written by citizen volunteers who were elected by the people, it sourced good ideas from all over the world such as rights for Nature pioneered in the Bolivian and Ecuadorian constitutions. Every evening the Constitutional Committee fed back to the people about their progress through an online process, and received suggestions from citizens who could engage in the process.

Although never ratified, the constitution is ready to go if future lawmakers choose to make it reality.

Iceland’s response to the crisis also differed from most of Western world in that they let the banks collapse. The government did not intervene to rescue them at taxpayer’s expense. The economy collapsed into a recession and inflation soared, pushing many into financial difficulty. But the downturn was over sooner than elsewhere.

“We were wise enough not to follow the traditional prevailing orthodoxies of the Western financial world in the last 30 years. We introduced currency controls, we let the banks fail, we provided support for the poor, and we didn’t introduce austerity measures like you’re seeing in Europe,” President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson said in January 2013 in Davos.

And in addition to not letting the banks take the economy down with them, Icelanders jailed the ones responsible for gambling with their economy. Several senior bankers were jailed for fraud, which again contrasts the experiences of countries like the UK.

Accountability is crucial for democracy. Even though disappointment of things changing slowly brought the Conservative party back to power in 2013, they had to go again once they had proved themselves not fit for the people’s trust.

Autumn this year, the elections will most likely see the old parties lose to a newcomer, the Pirate Party. One of its founders, WikiLeaks activist Birgitta Jónsdóttir, has been in the Parliament since 2009 and put forward legislation that is designed to make Iceland into a “transparency haven” by protecting freedom of information, expression and speech.

Iceland has a track record of electing top politicians from outside the established parties. The country’s President, elected as recently as on Saturday, is historian Guðni Jóhannesson: his areas of expertise are political history, diplomacy and the constitution. He has never been a member of a political party, but during his campaign called for a constitutional clause allowing citizen-initiated referendums over parliamentary bills.

Another post-crisis political earthquake swept through local politics in the capital Reykjavík. In the mayoral elections in 2010, each candidate was given the opportunity to use the online platform Better Reykjavík, allowing them to engage with voters who could submit policy suggestions to the site. Nearly half of the electorate visited the site, and 10% actively engaged by creating some 1,000 policy initiatives. Comedian Jón Gnarr, whose Best Party was the most active political party to use the platform, won the election and has since implemented several of the crowd-sourced policies, including more parks, improved cycling infrastructure, adult learning programmes and teaching financial literacy.

So even if England sends Iceland home tonight, the Nordics have certainly been worth meeting. On the pitch and in politics.