Climate change threatens all life on the planet. Only an equitable solution can solve it, argues Steve Rushton

This article was originally published on the independent journalism network Contributoria

“The rains come late. The sun behaves in a strange way. The world is ill. The lungs of the sky are polluted. We know it is happening. You cannot go on destroying nature. We will all die, burned and drowned”, states Davi Kopenawa, leader and shaman from the Yanomami nation, Brazilian Amazon, in a report by Survival International.

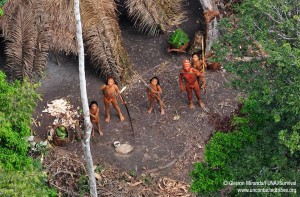

To the west, drought and logging are driving the uncontacted Mashco-Piro tribe off their land. Mainly living entwined with nature, indigenous peoples are severely threatened by climate change. First-nation advocate NGO Survival International reports climate change’s impacts include droughts in Amazon, Arctic meltdown, declining Sami reindeer herds and severe insect infections. This escalates destruction caused by colonialism and extractive capitalism, which has already created many ’sacrifice zones.’

The climate crisis is a culmination of the pollution since the industrial revolution fired up. Responsibility is vastly unequal; 20% of the world’s population created 70% of these greenhouse gases. Climate change threatens everyone, but particularly those in the global South. In 2009, Angelica Navarro, Bolivia’s climate negotiator to the UN asserted:

“Millions of people – in small islands, least-developed countries, landlocked countries as well as vulnerable communities in Brazil, India and China, and all around the world – are suffering from the effects of a problem to which they did not contribute.”

In polar contrast to the billions under threat, campaigners blame a small group of climate change profiteers for driving the crisis. The focus is on billionaires; the NGO Oxfam suggest that by 2016, 85 people will own more than the rest of the world.

The richest 1% feature in Outing the Oligarchy: Billionaires who benefit from today’s climate crisis. This far-reaching document by the International Forum on Globalization asserts: “Today’s single biggest threat to our global climate commons is the group of billionaires who profit most from its pollution and, in turn, push government policies that promote more fossil fuels.”

The same report details how billionaires often engage in lobbying to push dirtier fossil fuel expansion, such as tar sands. NASA climate scientist James Hansen is not alone in suggesting that if tar sands continue to expand it will be “game over for the planet.”

The global 1% extract wealth through global corporations. A Guardian article asserts that 90 corporations are responsible for two-thirds of man-made carbon emissions. A study by American MIT University substantiates the connection between wealth and pollution. The summary states: “Your carbon footprint impact rises with your income. The class estimated Bill Gates’ impact at 10,000 times the national average.”

The military industrial complex is also a key climate culprit; the US military is the largest polluting entity. A correlation can be drawn from the oil and war business. Evidence for this includes BP and Shell apparently lobbying the British government, before they invaded Iraq in 2003.

But these studies about wealth and climate change do not solely point the finger at the 1%: they blame the entire system. This argument has been made strongly in Naomi Klein’s latest book subtitled Capitalism vs. the Climate.

“Humanity confronts a great dilemma: to continue on the path of capitalism, depredation, and death, or to choose the path of harmony with nature and respect for life,” asserts the People’s Agreement, echoing the call for systemic change. It was drafted in 2010 in Bolivia by over 200 civil society groups and over 30,000 people.

The People’s Agreement envisions how those most to blame for the ecological crisis do most to fix it, through the conceptual tool of climate debt. It calls on the world to find a balance with nature, by finding an equitable relationship across humanity. Polluter must pay is the solution. The initially industrialised north should sharply reduce its carbon output and “decolonise the atmosphere”, in tandem, taking measures to assist the majority world progressing whilst they forgo emitting their ‘fair share’ of carbon. It also demands climate refugees are given asylum and poorer countries are assisted in adapting to climate changes impact.

If you accept manmade climate change, these points are fairly irrefutable. Naomi Klein suggests climate change’s threat to the status quo explains why elites invest so much into climate denial.

Considering the billionaire owners of industry adds another layer to the climate debt framework. The rich north holds most responsibility for climate change, but even here, responsibility largely lies with the billionaires and multi-millionaires. This global 1% will soon have amassed the same wealth as the 99%. The stark inequality and poverty in ‘rich countries’ shows that oil-based capitalist extraction has not enriched everyone. And many examples of climate victims can be found in marginalised communities in rich countries: coal miners that die young with damaged lungs; or Hurricane Katrina’s impact on black and poor communities in New Orleans that shows how swathes of ‘first world’ communities are increasingly in the climate change frontline.

Effective climate mitigation means leaving most of the carbon in the ground, stopping the dirty energy lobby and creating a sustainable economy, based on viable green alternatives. Practical necessary steps include banning new dirty energy projects, real limits on northern country emissions and a carbon tax charged per ton of gas emitted.

Climate debt based mitigation and adaption means redistributing the wealth of the 1% who made their money from fossil fuels to those they impoverished. There are many possible mechanisms, such as ending the government subsidies to fossil fuel companies, a transaction tax on financial capital flows and closing tax havens.

Once you consider climate debt, it is hard to ignore how the global elite’s wealth has been built on the back of exploitation, dating back to slavery and colonialism. In terms of debts today, the world seems upside down: the global South is expected to repay massive sovereign debts, even though these debts are often unjust, occurred without the consent of the people and without benefiting them.

The Philippines’ debt burden is an example: at around $60 billion – with daily debt repayments of $22 million (2013 figures) – it is the legacy of Dictator Ferdinand Marcos, 1965-86. Increasing the injustice, the nation frequently bears the onslaught of climate change. In 2013, Typhoon Haiyan killed over 5,000 and made as many as 4 million homeless. It will also cost hundreds of millions, if not more, to reconstruct devastation. Philippines’ unjust debts are spiralling further, due to the cost of typhoons escalated by climate change.

Before Haiyan the nation was hit by Ketsana in 2009, at the time one of the worst ever to hit the capital, Manila. Reflecting about it and the ever-escalating typhoons the Debt Resistors Operational Manual, written by the US group Strike Debt, asks: “Why should Filipinos, who on average emit 0.9 metric tons of carbon annually, pay for the destruction wrought by people in nations like the US, who emit 17.6?”

Global justice campaigners also assert that international financial institutions – like the IMF and World Bank – have worsened poverty in countries like the Philippines: not only by restructuring the dubious debts, but also with austerity stipulations. Additionally, evidence suggests austerity reforms can drive climate change, pushing further carbon intense resource extraction, cash crops, dirty energy projects and cutting back on green subsidies. Within a climate debt resolution any international institution’s programme that exacerbates climate change needs to be terminated and reversed.

During 20 years of climate change reductions negotiations, 1992 greenhouse gas levels have nearly doubled.

The People’s Agreement from Bolivia states: “The recent financial crisis has demonstrated that the market is incapable of regulating the financial system, which is fragile and uncertain due to speculation and the emergence of intermediary brokers. Therefore, it would be totally irresponsible to leave in their hands the care and protection of human existence and of our Mother Earth.”

In essence, it seems obvious that the ‘logic’ that has got us into this situation – free trade, deregulation, privatisation – will not get us out of it. Simultaneously, that it still dominates shows the power of those pushing this narrative: the fossil fuel billionaires.

Instead, the concept of climate debt provides a platform to drive humanity on progressive ideals of morality and justice – not least respecting indigenous peoples land rights.

Solutions do not revolve around throwing money at problems. What indigenous (and rural) people that are still self-sufficient with their lands (like the uncontacted tribe from Brazil pictured above) need is not handouts. They need the rest of the world to stop stealing their resources. In symbiotic fashion, the world needs these peoples’ lands not to be destroyed. The vast majority of rich bio-diversities today are indigenous peoples’ lands.

Climate debt’s holistic nature makes it a potential pivot to build meaningful climate action. The 1% needs to take a massive hit, but for the majority even in the industrialised north it could make society far fairer, ending the seemingly never-ending story of austerity.

To repay climate debts, the majority needs to reclaim democracy from the big oil oligarchy and stop any more dirty energy extraction. Instead we need community-based renewables . We need to reduce consumption, but this could come with benefits. Buying local and a truly fair trading system could revitalise economies and help tackle inequality where global free trade is failing; by tackling climate change we could reduce the price of living via re-nationalising transport, housing, energy and water. Instead of being driven by profits, our society could be focused on people and planet.

There are alternatives. But to create a sustainable world the climate movement must swell and galvanise to make the 1% pay their climate debts.