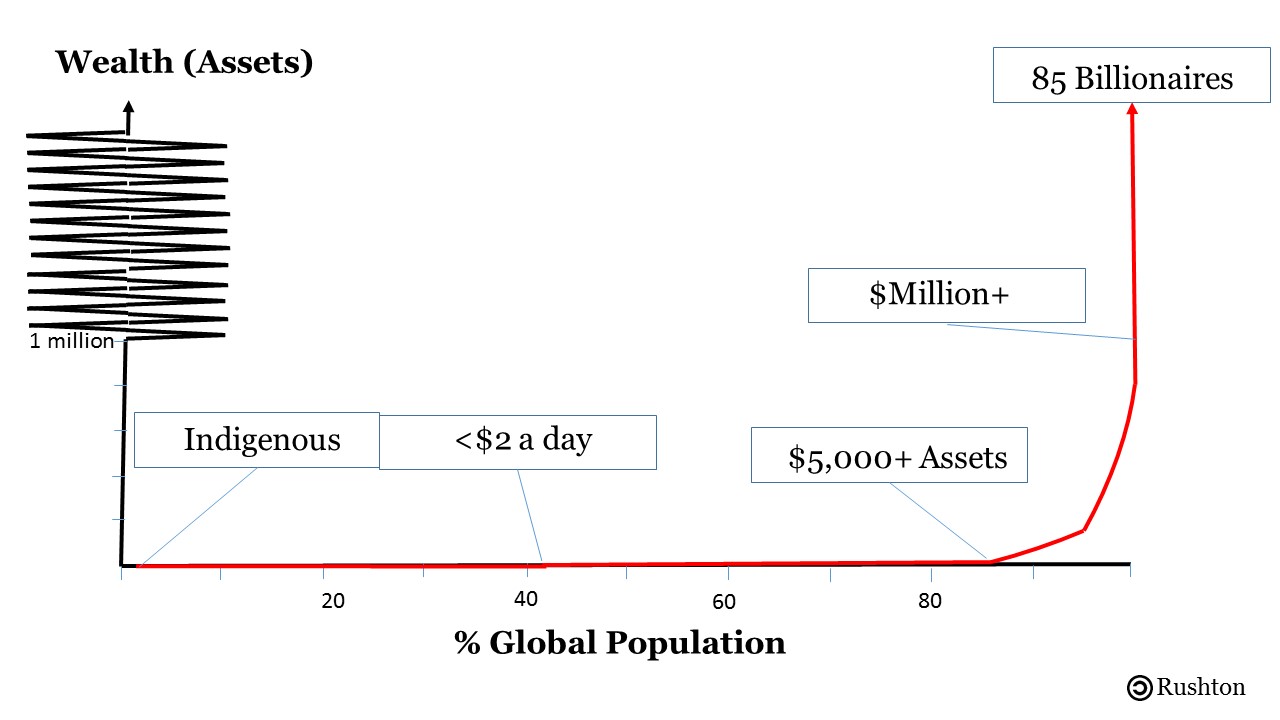

In an ever-increasingly unequal world, 85 people are predicted to soon own the same wealth as the poorest 3.5 billion. There are a further 12 million people with assets $1million plus: they account for the global 1.5%. Around the world one billion people – 15% – are counted as being in the world’s middle class with assets over $US 5,300, whereas globally 2.8 million (40%) live on less than $2 a day. To some extent off the spectrum, there are around 150 million indigenous peoples (or 2.5% of the population), many living without money beyond the capitalist system, but many too under threat from this system.

Inequality deserves far greater consideration by the climate movement; studies suggest that a person’s carbon footprint generally is tied to their wealth. This expands on research I have undertaken on Climate Debt: a conceptual tool that asserts the polluters must pay for climate change and its impact.

The consumption of billionaires partly explains their enormous carbon footprints. But even those that do not take helicopter rides from their super yachts to luxury islands are likely drivers of climate change. They are extremely rich from investing in the world’s largest corporations that are mainly carbon intensive, including petro-chemicals, the military industrial complex, from mining to agro-business. Research shows the largest 90 corporations create two-thirds of cumulative carbon emissions.

The lobbying power of the mega-elites presents another severe problem for the climate movement. The super-rich hold extensive sway from owning and funding the corporate media, academia, advertising and politicians. Five billionaires, for instance, own between 70-80% of Britain’s mainstream press. Billionaires pump millions of dollars (and pounds) to create climate change denial. Intense and extensive corporate lobbying pushes governments towards trade deals that enable further dirty fossil fuels and climate threatening projects.

Supporting the billionaires in crude terms, pun half intended, millionaires also are massive emitters, again through consumption and the means of their wealth. Of course a great deal of the world’s richest 1.5% directly in fossil fuels and have their wealth invested into oil. But also many drive carbon emission without direct contact with fuels. Three illustrative examples are a PR executive, a property landlord and a pension firm investor.

The PR executive makes adverts to push consumption and attempts to create a social licence for corporations, all to maximise profits, be they runway projects, disposable products built in sweatshops or an array of other carbon intense products. Our hypothetical property landlord could make their homes eco-efficient, with insulation, but instead syphon more profits from the tenants. A trend is emerging: the rich can get richer by forcing people lower down the wealth curve to increase their personal carbon footprints. When it comes to our pension investor, this financier is investing public sector workers salaries into fossil fuels. Of course in the millionaires’ brackets there may be some people discouraging climate change – perhaps, the owner of the wind turbine business with low personal consumption – but these people are exceptions.

Moving on to a worker struggling on an average wage, their carbon consumption is harder to gauge. It may be dragged up through circumstances beyond their control – for instance, rented accommodation with terrible insulation. Some on this wage may consume far higher than others, for instance, buying disposable consumables made in sweatshops or constantly go on cheap flights, whereas another might buy buys stuff that lasts and opt for coach travel. What is interesting essential, from a climate perspective, is that quality of life could improve even if their carbon consumption was reduced.

Let us imagine that they changed their energy supply from one of the Big Six energy suppliers, instead buying power from a renewables cooperative. If not for profit renewables were allowed to flourish, the price would drop. This argument is made by Fuel Poverty Action, a leading campaign in terms of tackling both climate change and poverty simultaneously. Yet currently big business is pushing to remove these opportunities, with deals to lock Britain in gas and nuclear instead.

Those earning less than $2 a day account for an even larger proportion of the world’s population and are far harder to generalise. But we could imagine a sweatshop worker and a coal miner. Both are exploited to work within the globalised carbon intense system, so we will not count this in their climate footprint. Depending on where they live, their actual carbon footprint may be as little as the gas they use to cook.

The final grouping is far smaller, it is the indigenous people that live on and beyond the fringe of capitalist extraction. On the graph above, I have drawn a dotted line to indicate that these people may have a negative carbon footprint. Their ways of live have engendered some of the world’s richest bio-diversities, for instance the rainforests that act as the ‘world’s lungs’. Often these lands are under threat from the global system’s level of consumption, for the raw materials that are sent to the sweatshops, to make the disposable products for consumers in the West – all of which comes at the price to the many for the profits of the few.

Overall, repeatedly, what is happening is that the current system works in the interest of a small number of people, syphoning wealth up the curve – pushing the billionaires to new heights. In turn, it leaves the majority in more poverty. We need to think beyond this system, but those with the money are those with the power.

Last year, Naomi Klein further popularised the idea that it is climate change vs. capitalism, considering the interlinked role of capital, wealth and political power perhaps it’s time to consider how it is the climate movement vs. the billionaires.

3 thoughts on “To tackle climate change we need to challenge the power of billionaires”

Comments are closed.